|

|

|

|

|

McQuilkin,

an award-winning poet and former director of the Sunken Garden Poetry

Festival, thinks of "Counting to Christmas" as a gift to friends,

both known and unknown, at Christmas time. Though many of the book's poems

have appeared in publications such as The Atlantic Monthly, Poetry,

Prairie Schooner, The Christian Science Monitor, and Yankee,

they were originally written as Christmas cards over a period of 25 years;

and McQuilkin hopes they will carry some of their original intent. The

contents of the book are arranged in a sequential pattern, beginning early in

December and progressing to Christmas Day. The poems may be read much as an

Advent calendar is opened -- one a day during the pre-Christmas season.

Printed on heavy, textured stock, this gift book is a work of art and

contains a number of poems based on works of art. The collection is marked by

both wit and lyricism, and is secular in tone -- one poem depicts a Zuni

solstice ceremony and many others focus on the natural world, although a good

number of the poems present traditional Christmas motifs. Read

some sample poems from the book. |

|

BOOK

STATISTICS ISBN:

0-9662783-3-x

|

CELEBRATION A dozen apples in

December shrink and wrinkle, go

from dark to darker, hang by

threads no thicker than our own. And yet how like to

ornaments a dozen apples in

December and how the sparrows,

reeling, wassail on the earth-gold

wine a dozen apples, aging,

brew beneath a low and

southern sun. |

|

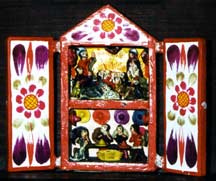

GETAWAY after an

early work by Mack Burns, age 4 He crayoned

his first cr¸che in three parts. All’s

well at the top—the Firmament is solid:

heavenly blue. But the sky is trouble. It’s

full of what—stars or angels swarming

like a plague of leggy spiders. Just

above the manger is a star burst of

yellow from something like a Scud incoming. Part Three has the Baby Jesus the size

of his parents, his feet and head protruding

from a purple perambulator. A lush

brown, black-haired Mary, her arms

and one leg colored jaggedly, leans

forward as if to wheel the giant baby, hissing

to the blueblood blob of Joseph “Let’s

get out of here!” The

space around the shed is fire-orange except

for a—camel? Brown as Mary and

humped high as the ridgepole, it’s

kicking a hole in the siding. To knock sense

into Joseph’s head? Or show it’s

raring

to go? Maybe left by a Wise Man after he

informed on the king. But— shouldn’t

it be a donkey? A minor mistake. Thank

God for its headstrong headful of a stall somewhere Herod never heard of. |

|

NOELING

IN THE HOOSEGOW for

Gladys Egdahl When the church burned down that December, town hall had to serve. Rose pumped an old foot-organ so hard she pounded the floor above the heads of the drunks in the lock-up below. She meant it, was fiercely in favor of God but not of how when God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen ended, it didn’t in the underworld, accompanied by banging and jangling of bars, slurring into Away In A Manger off key but softly softly, until Rose played along. This time she did her pumping gently. Being six, I said it was wise men. No one said no. |

THE REVEREND ROBERT WALKER

SKATES

on

Duddingston Loch at sunset in

black—black top hat and frock coat, britches,

garters, stockings, skating shoes black.

Except for pink laces and the flush

on his face, slightly deeper at the

ears, he is

black as his Advent sermon. Oh yes,

his scarf is white. And if I say the ice is

black, I mean it’s not, is in fact a window

for fish. The

Reverend has turned his back on the sky between

the hills, which is the color of his ears. His

right leg is raised, extends behind him like the

long tail feathers of some exotic bird. He is

leaning into the wind, leading

with the sharpened blade of his nose, arms

wrapped one inside the other. Or so

Sir Henry Raeburn, R.A., did him in oils,

c. 1794. Those

fine cross-hatchings on the Loch are not

from all the Reverend’s parishioners celebrating

after service, skating up a storm, for the

hills and the sky seem no less skated

upon. It’s

Time. As surely as ice, oils crack. Nor is

the clerical top hat what it was. Look closely.

You’ll find the ghost of its earlier brim, painted

out imperfectly, is aimed low as if a

moment ago the vicar was searching for a

flashy trout. He has,

it appears, raised his sights to the deepening blue of night,

or something more distant. He dedicates a

miracle to it, no major miracle, mind

you, but still he makes his turn (notice the

sliver of ice kicked up by the heel of his

skate), has all but completed the figure

6 he means to raise to an 8. |